We recently had a stereoscope and a few slides donated to our education programs. If you are unfamiliar with stereoscopes, they look like an old fashioned viewfinder, with a handle on the bottom and a stick coming out of the front. Slide a card into the slot, adjust the distance, and presto: you are treated to a 3D scene of a fairy tale or far away land.

Children love stereoscopes. They have the allure of seeming old and valuable, combined with the modern magic of 3D technology. In essence, stereoscopes were the virtual reality headsets of the Victorian age and they have maintained the ability to captivate audiences of today. Bring a stereoscope into a room full of first graders and they will eagerly gather around. The lucky student who gets the device will methodically look at slide after slide, accidentally smacking their neighbors with the handle as they remain lost in the world of yesteryear. This will continue until the pleas of their classmates to take a turn win out, and the stereoscope is transferred into another set of hands. Even safely in my thirties, I couldn’t resist looking at every slide that accompanied the stereoscope that was brought in last week.

For all of their glamour, stereoscopes are fairly simple. We humans have two eyes, each in a slightly different place. Each eye takes in our world at a different angle, and our agile brains combine those views into one sensible image. In other words, we always have stereoscopic vision. It gives us our ability to perceive the world in three dimensions. Without this knack, it would be very challenging to drive, catch a softball, or even thread a needle.

When you look through a Victorian stereoscope, you are viewing a card called a stereograph on which two slightly different photographs of the same scene are printed. The stereoscope forces each eye to take the pictures in through a separate glass lens. These lens are focused inward, forcing your eyes to combine the images at a single point. Add in our brain’s natural 3D powers, and voila: you see an illusion of depth.

Stereoscopes were one of the great fads of the past. The ability to create a stereoscopic illusion was first documented in 1838 by the British scientist Charles Wheatstone. His writings on the ocular trick were interesting, but not much was done with them for another decade. Then, scientist David Brewster refined the design, crafting a hand-held device you could raise to your eyes. This device, combined with the newfangled invention of photography, created a stereoscopic fad that swept the world. By 1856, the London Stereoscopic Company had a catalog of over 10,000 stereograph cards available for purchase. Six years later, their listings had grown to over a million.

Stereoscopes were marketed as a way to bring families together. Advertisements showed grandchildren and their elders smiling as they enjoyed their parlor stereoscopes. They were also billed as a way to view the mysteries and wonders of the world without leaving the comfort of your living room. In a time without the internet, televisions, and even widespread to access volumes of photography, the stereoscope must have truly seemed like a doorway to the globe.

These wonders did not stay in the home. By the late 1800s, stereoscopes were being aggressively marketed to schools. Like the educational technology and gaming companies of today, stereoscopes were pitched as a way to make the doldrums of learning adventurous and fun to pupils. It was said that by learning through a stereoscope, the chaotic or unfocused child would be shielded from the distractions of the classroom. The American stereoscope company Keystone developed a stereoscope based curriculum known as the Keystone system. Soon, the company claimed that every American city over 50,000 was using the Keystone system to teach pupils in their public schools.

As always, some spectators of the stereoscope fad were alarmed. They worried that the stereoscope would replace books, and students would come out of school only able to learn through a series of images rather than mastering the complex skills of reading and writing.

Eventually the fad waned. This was not due to the consternation of educational naysayers, but because it was replaced by a new parlor novelty: the radio. In spite of this, the technology was not left behind in this craze of the past. Stereoscopic vision has periodically resurfaced in trends, from the red and blue 3D movie glasses of the 1950s, the headache-inducing magic eye books in the 1990s, and finally in the 3D video games of today. The magic of stereoscopic vision seems here to stay.

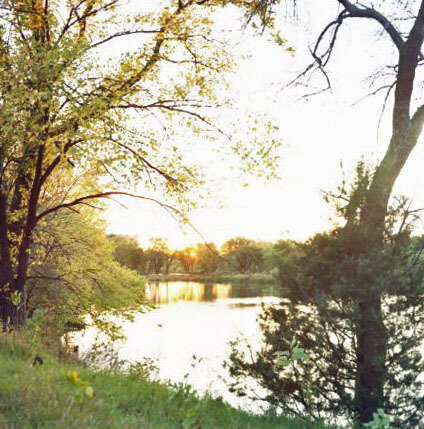

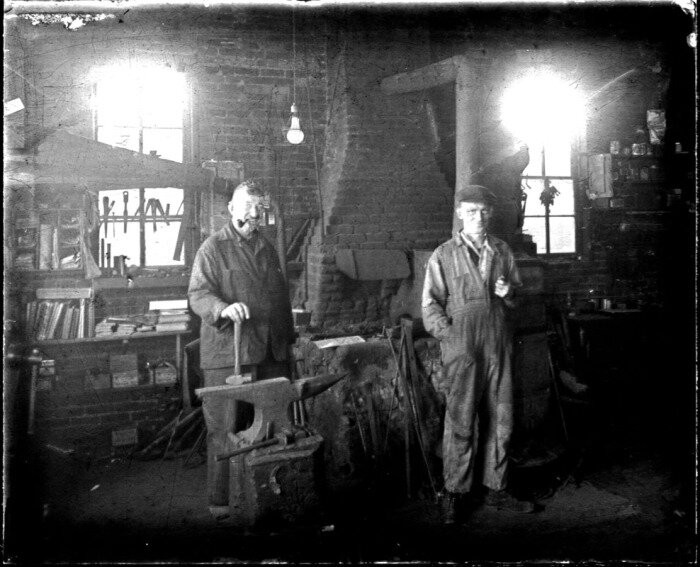

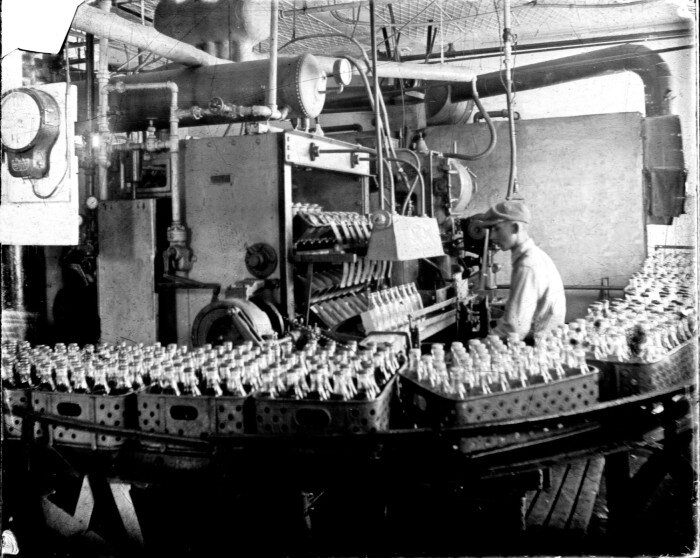

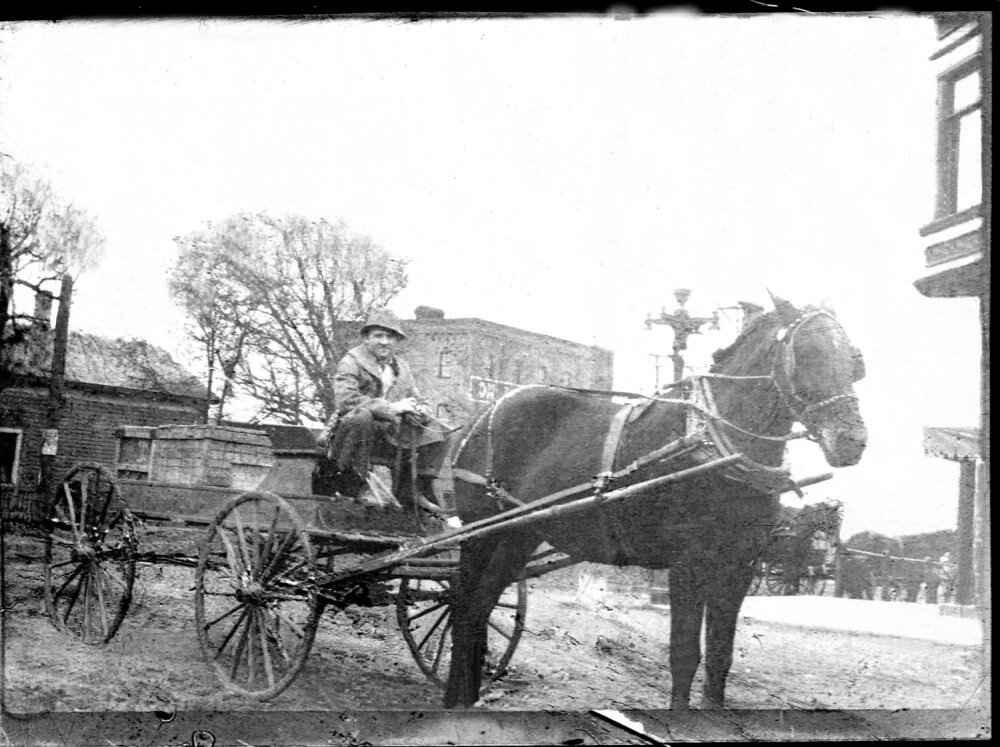

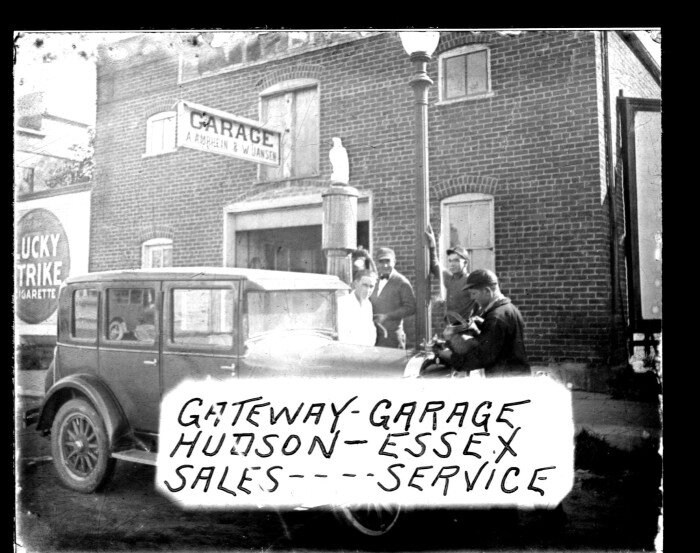

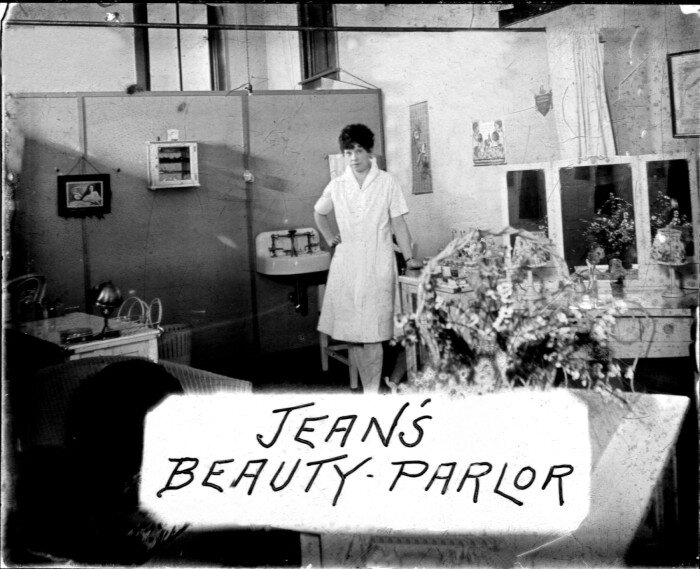

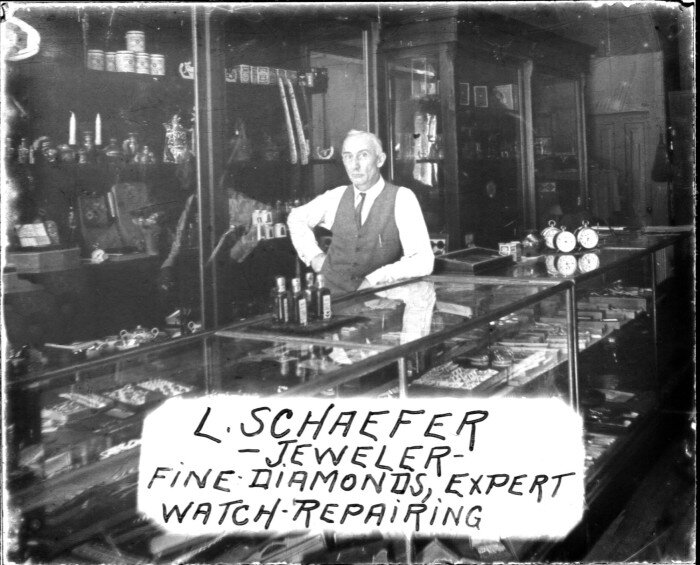

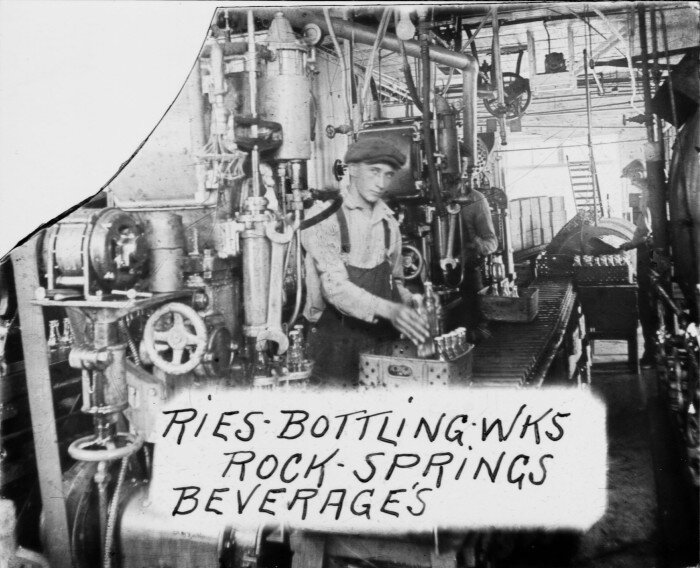

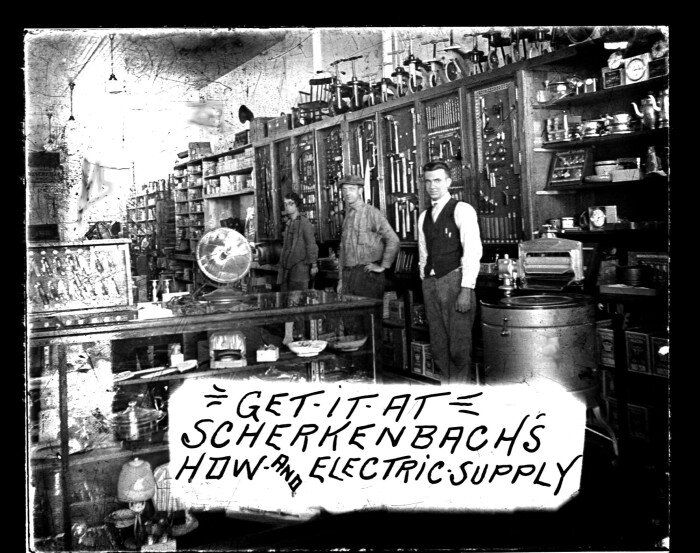

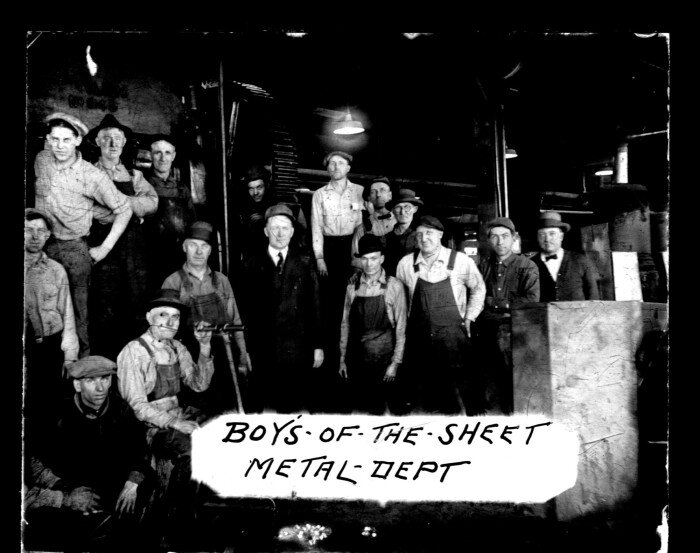

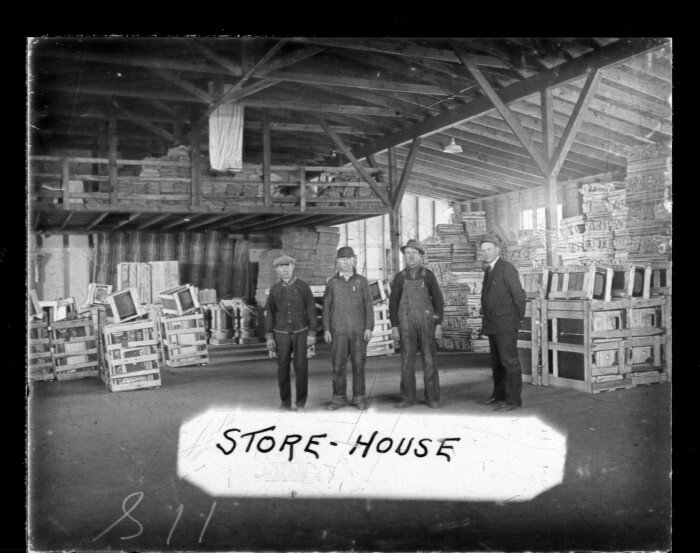

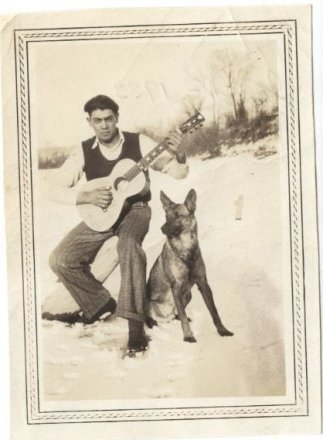

At the Scott County Historical Society our collections feature many stereographs, the dual image cards that make the magic of stereoscopes appear. Some were owned by county residents, transporting them to far away places. Others show scenes closer to home depicting neighbors or local buildings. Still others tell scandalous stories or humorous tales. If you are interested in trying a stereoscope for yourself, stop by and ask! We will pull it from it’s home in the education closet, and give you the chance to step into another world.

Below are a few of the stereographs that have a home in the SCHS Collections.