In the late 19th century into mid 20th century Shakopee was the home of a booming industry. In the times before electricity really got a hold in America, the tools for cooking and heating relied on wood or coal with gas becoming popular later. Stoves and ranges that these fuels were loaded into were heavy metal constructions that looked quite a bit different than the typical box stove/oven combos that we see in our modern kitchens. Here, in the northern portion of the Midwest, such heating implements were in high demand but there wasn’t really a big Midwestern stove and range producer until 1891. The year 1891 marked the beginning of the Minnesota Stove Company, and once it started, it took off.

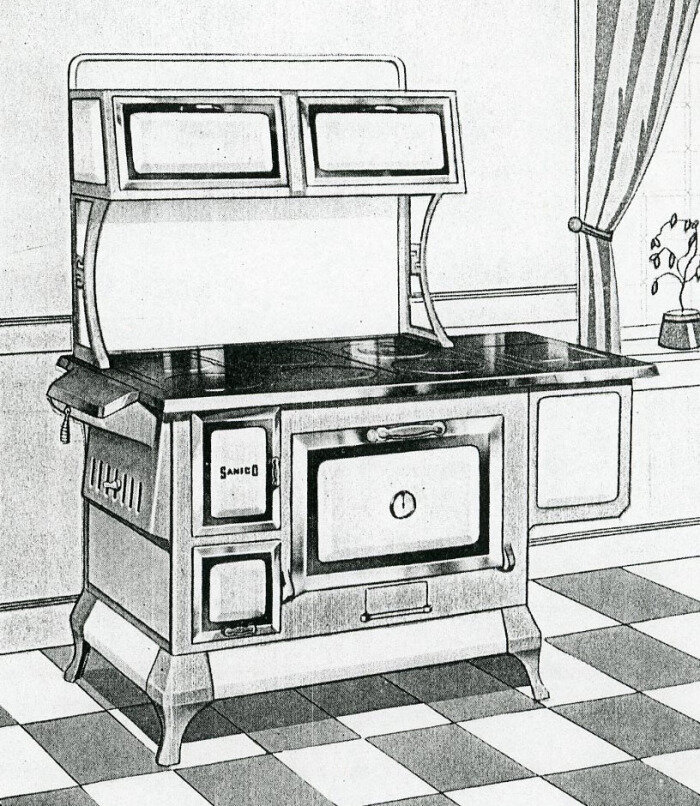

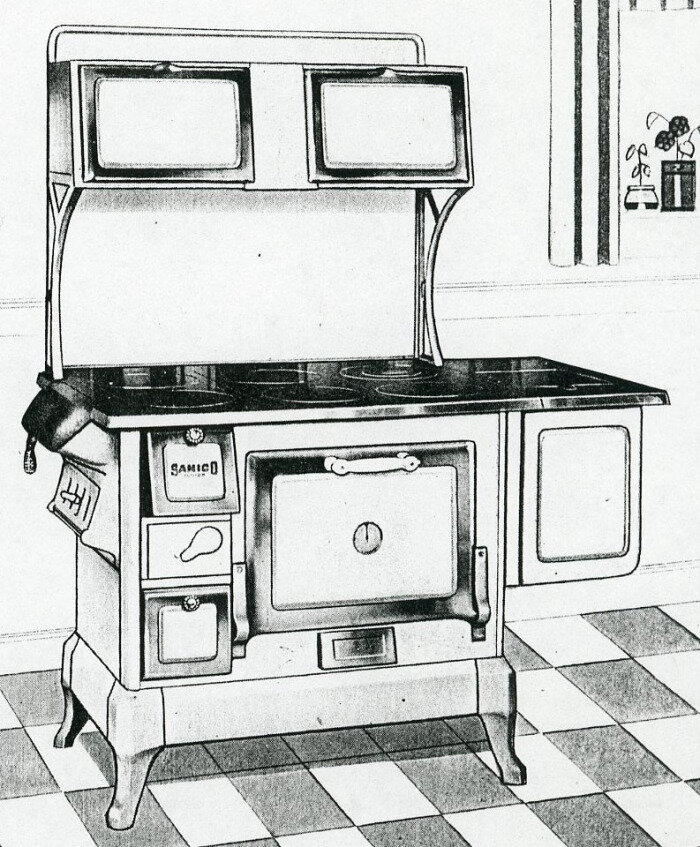

In May of 1891 Henry Hinds, Theodore Weiland, and Julius A. Coller returned to Shakopee after being appointed to inspect a stove and general foundry in Ohio. They were sent to determine whether or not a proposition to open a similar business in Shakopee seemed a wise thing to do. Their reports returned satisfactory and the plans to build the Minnesota Stove Company were put into action shortly thereafter. On September 19th of the same year the foundry was built with the first smelting taking place on November 23rd. Some of these early stove styles were the “Steel Coral” stoves. These stoves, unlike later stoves, were highly decorated.

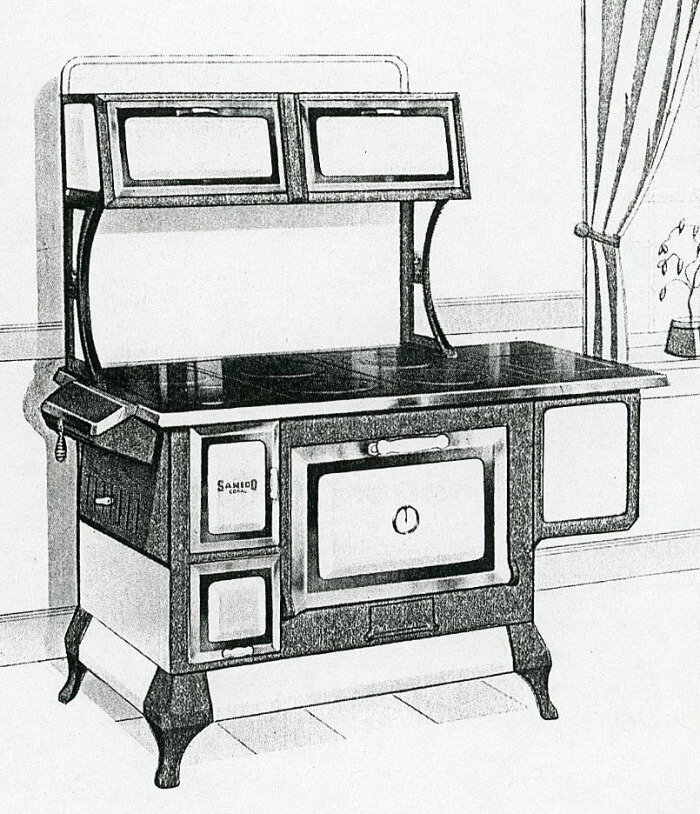

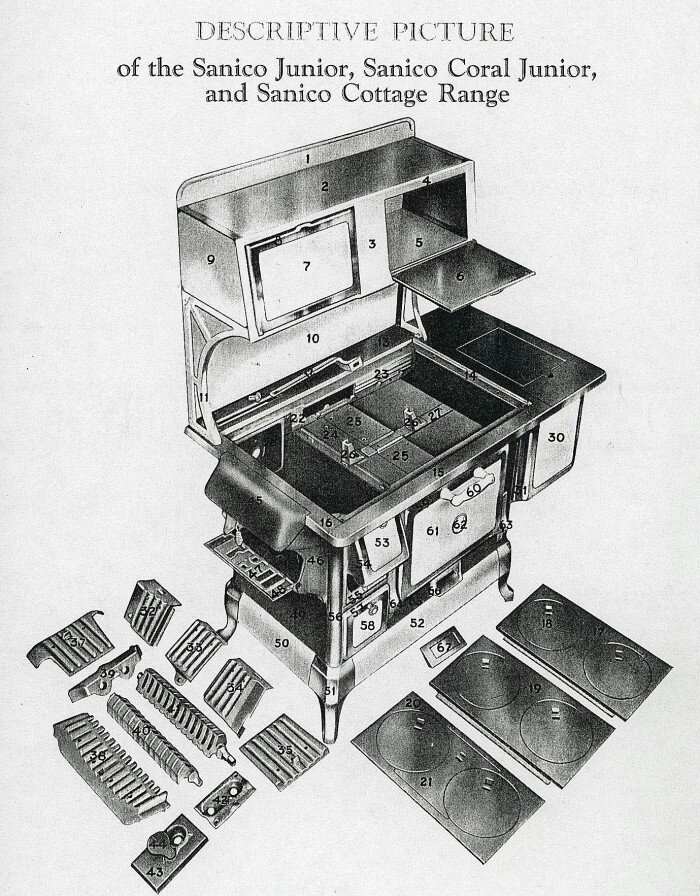

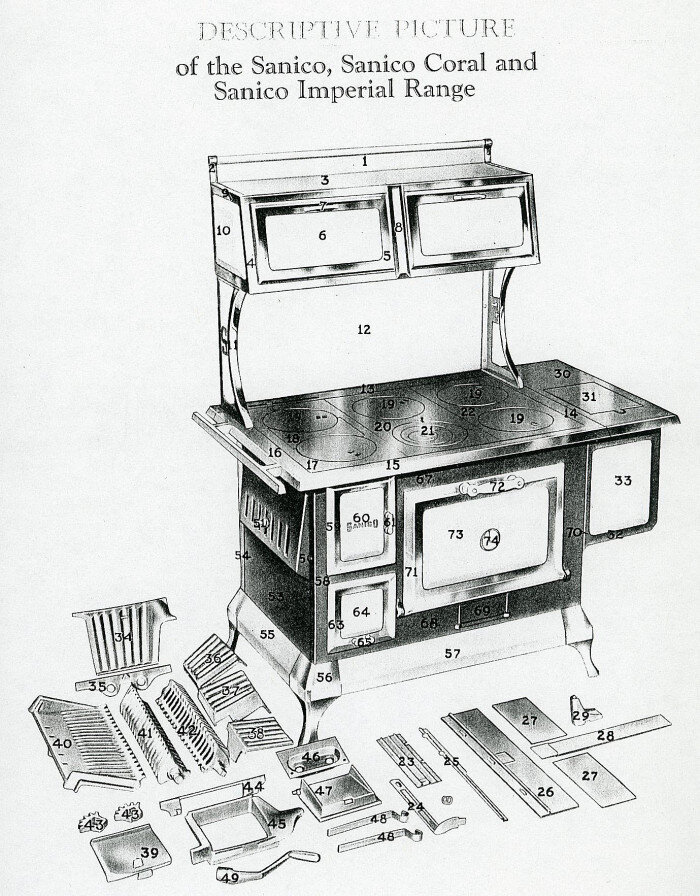

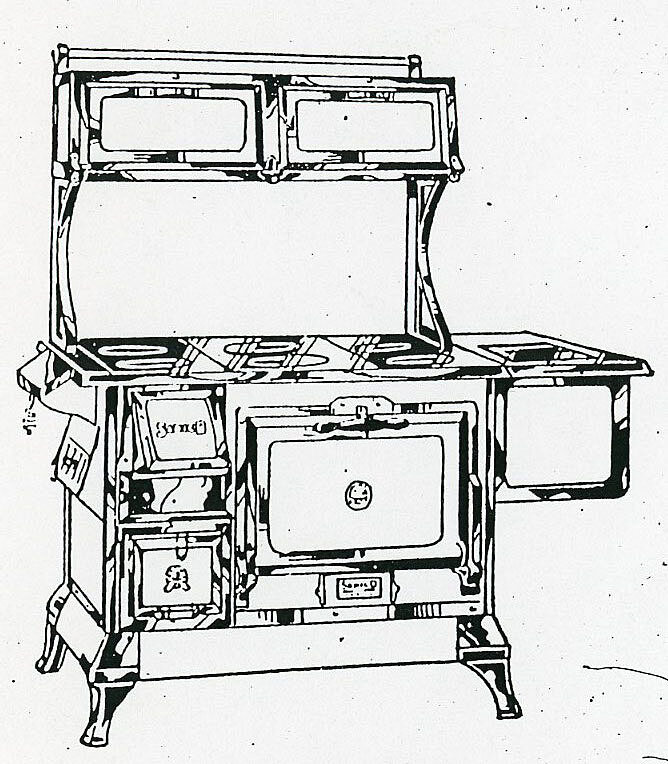

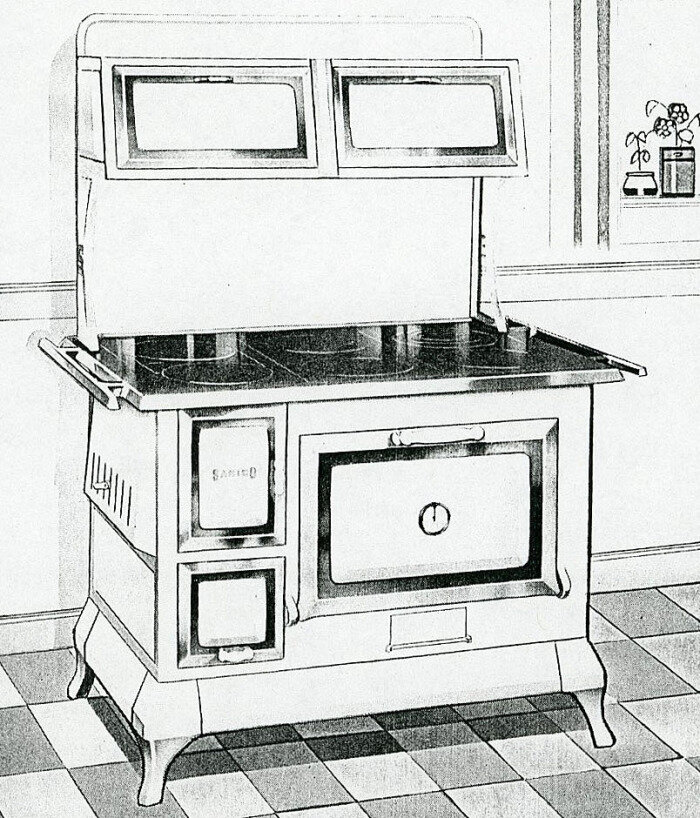

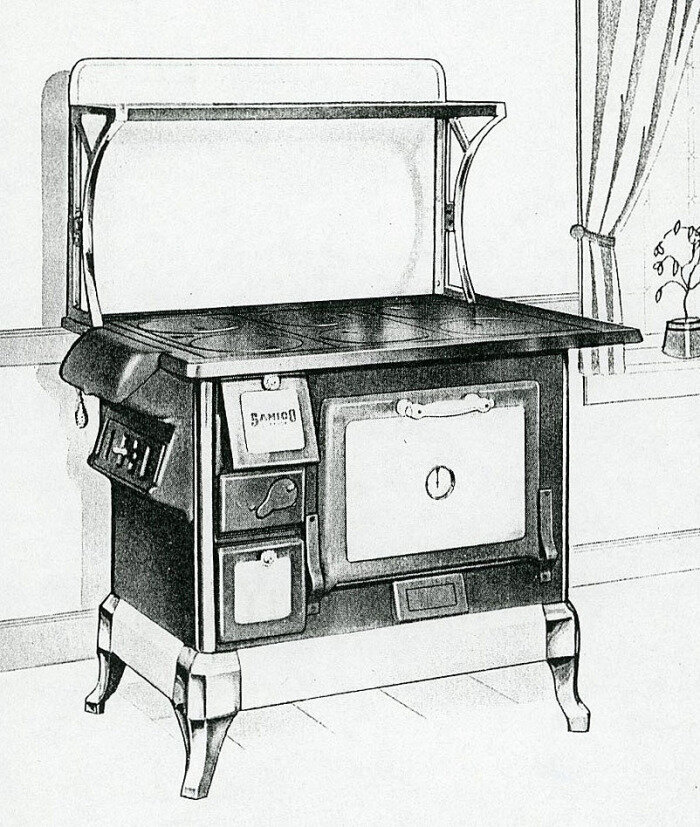

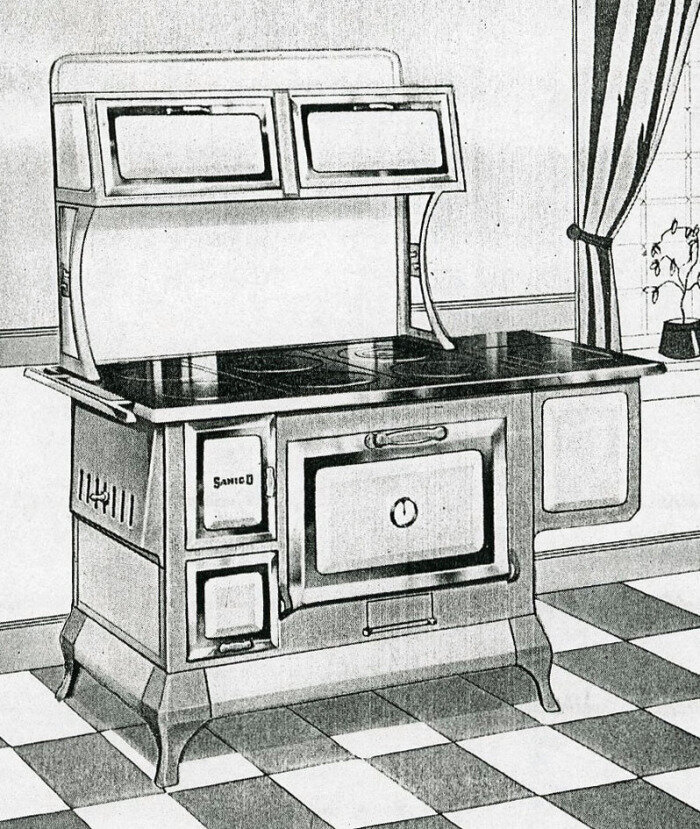

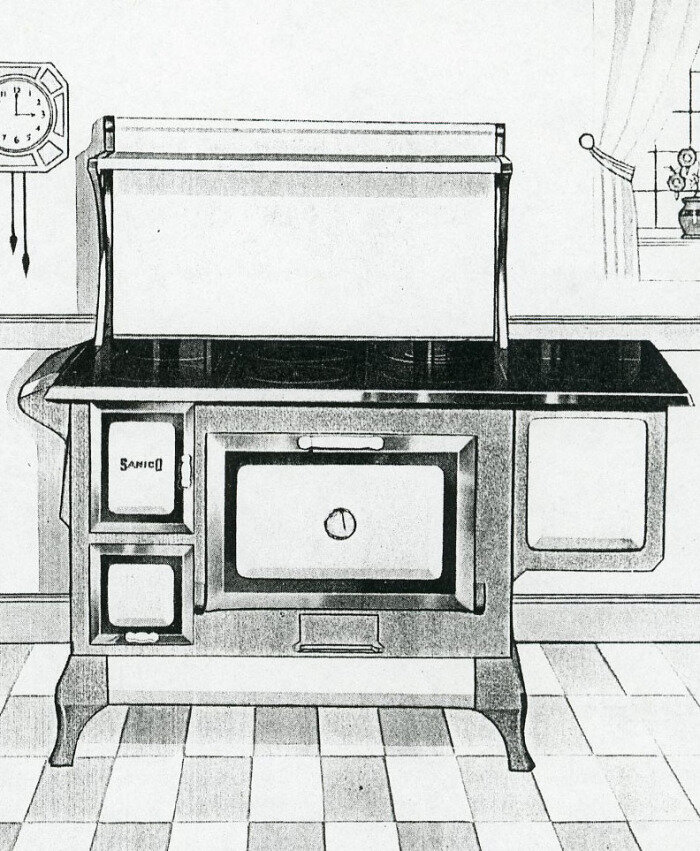

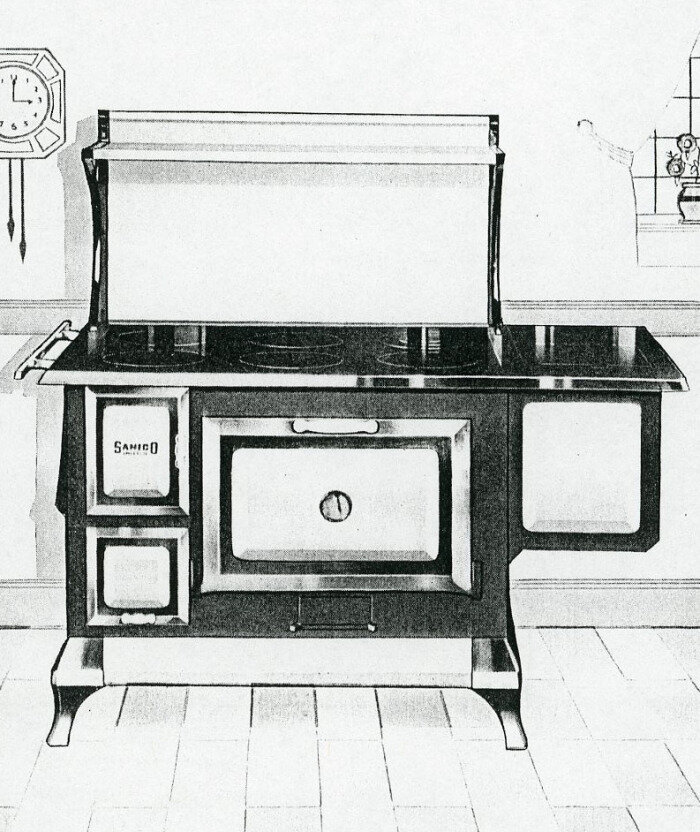

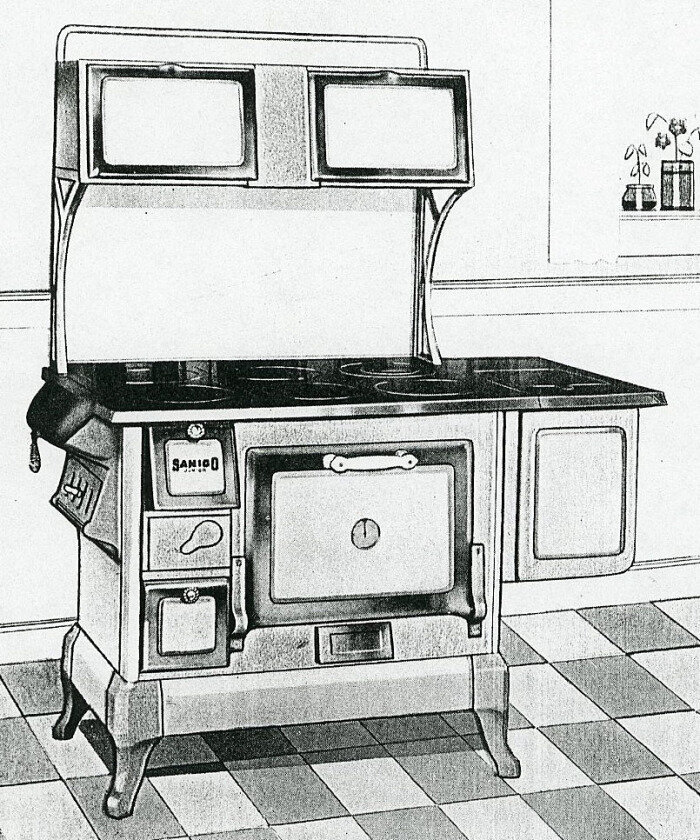

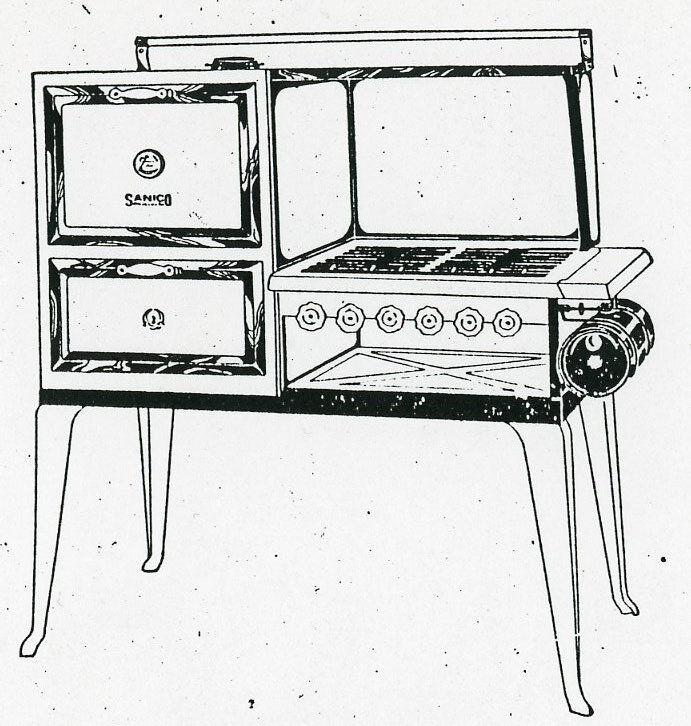

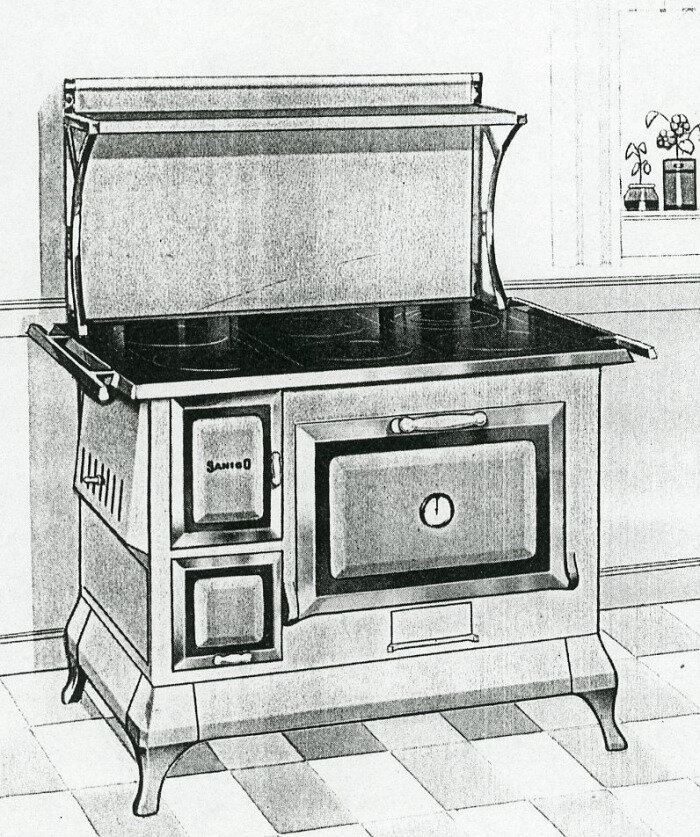

The cold northern weather and the lack of stove companies pushed the Minnesota Stove Company to early success. A 1906 copy of the Scott County Argus stated that 100 stoves were sold from one advertisement within two hours of leaving the press. Due to these successes, the “Imperial Coral” stove was added to the production line and in 1908 the foundry was expanded. A 12,000 square foot brick building was added to make the total size for the company 60,000 square feet. They also increased the number of employees. What had started as a 35 person operation was increased to 85. By 1908 the company had “more than 150 styles and sizes of stoves” to claim. Some of these were the Sanico, Steel Coral, and Son Brands stoves. In 1911, the company was overhauled. They had a new cupola made and new machinery installed.

The Sanico line.

Things continued to go well until 1914, where the Minnesota Stove Company ran into one of its first hiccups. The company closed in December of 1914 due to an issue with union workers and they stayed closed for about two months. They closed again in March of 1915 due to similar issues. They opened again on April 15th of 1915 with a crew of non-union workers. By October 1915 they were employing 125 workers and business was booming once more. An October issue of the Scott County Argus stated, “The company is today one of the chief manufacturing industries of our city and one of the leading institutions of its kind in the Northwest.”

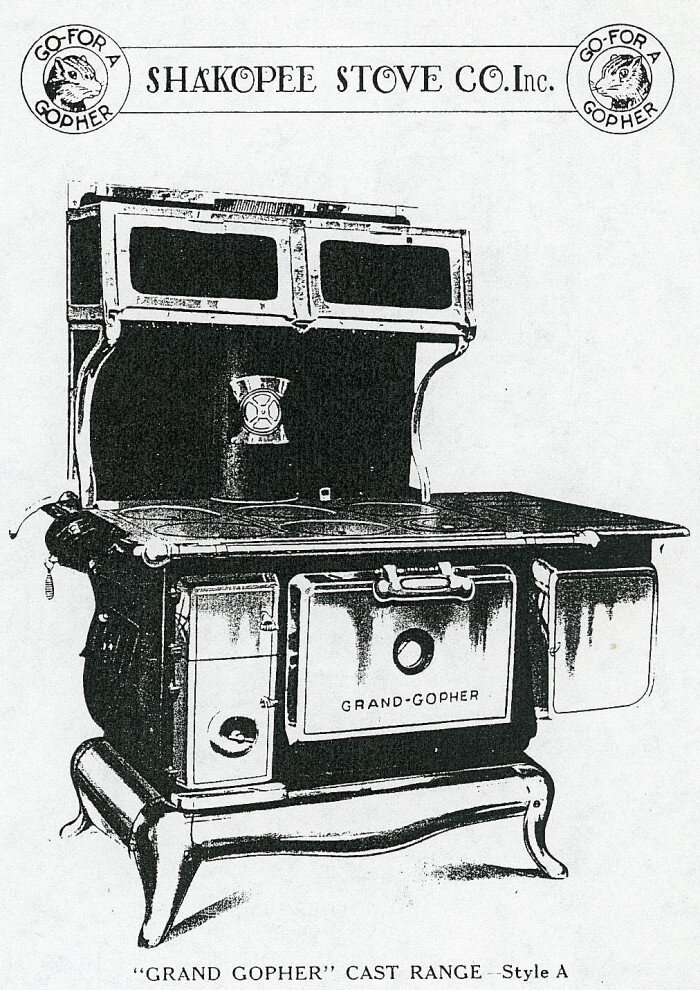

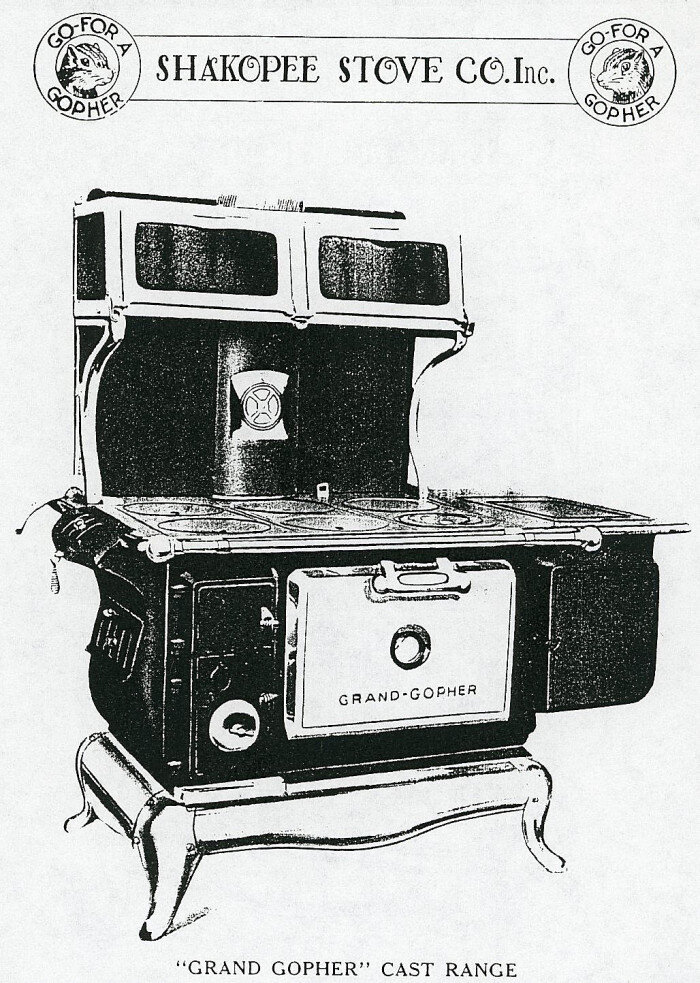

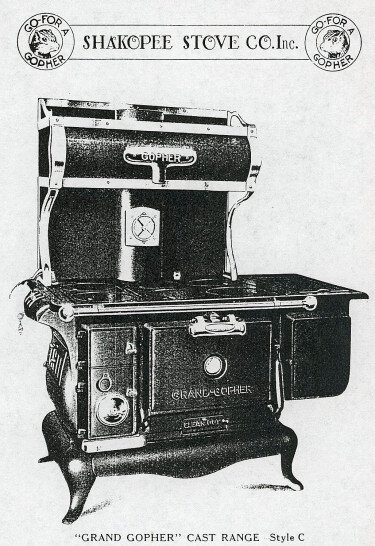

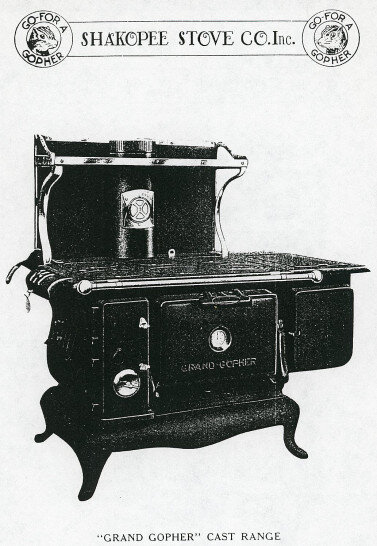

Looking at the successes of the Minnesota Stove Company, a second group of men looked to open a stove and range company of their own. In 1915 J. Warren Hawthorne, George G. Reis, W. T. Curry, and Rudolph T. Selbig incorporated the Shakopee Stove Company, what was originally going to be called “Equity Stove Company,” and produced their Gopher line of stoves and ranges.

Work in the foundry of the Shakopee Stove Company began on October 28th of 1915. Finished products did not begin rolling out until mid November due to the late arrival of cleaners, nickeling equipment, and polishing equipment. These stoves were designed by the four men that had incorporated the business. They were with little decoration so that parts could be easily repaired and replaced. Much like Minnesota Stove Company, business at the Shakopee Stove Company took off. Fortunately, demand for their products was so high, both companies were capable of existing in Shakopee without interfering with each other. In fact, before the Shakopee Stove Company was even completed, they had orders for each of the items in their product line. People were so impressed by the Shakopee Stove Company’s work that the Waterbury Furnace and Heating Company of Minneapolis moved orders for foundry work from an Iowa company to the Shakopee Stove Company.

In 1921, William Spoerner stated that the Shakopee Stove Company could not meet demand despite having recently added two expansions. A newspaper reporter referred to a statement by William Spoerner saying “…he is not able to supply the demand with the limited capacity of the plant. He says if he had the room he has orders enough to keep a force of twenty-five full-fledged molders busy every day.” Part of the problem the Shakopee Stove Company had was that they had no where else to expand to. They had other companies working near them and while they were looking to expand to a plot of land past the railroad, they did not end up working out a deal with the owners.

While the Shakopee Stove Company was having its troubles keeping up with demand, the Minnesota Stove Company had problems of its own. On March 1st of 1923 there was an explosion in the casting room at the Minnesota Stove Company that was likely caused by a spray used for castings coming in contact with an electric stove. The explosion started a fire that spread to the assembling department and warehouse. Firemen were able to prevent the enameling department from getting caught up in the blaze. The total losses amounted to $150,000 that was only partially covered by insurance. Despite the fire, business wasn’t too harshly affected. Employees were back to work by March 12th and damaged stoves were sold off at a reduced price.

On March 16th of 1923 they set plans into motion to expand their enameling department. Within one year, business was high once more despite certain areas within the factory still being shut down. In March of 1924 they organized a 150 person fire company and fully equipped the building with fire chemicals and a new hose to prevent future fire problems. Unfortunately, later that year, the Minnesota Stove Company ran into a second problem. It was the same problem that the Shakopee Stove Company was having. Demand was high. Too high. The Minnesota Stove Company was not able to keep up and was declared bankrupt October 27, 1924. This was not the end of things though. The people of Shakopee had seen their stove company do a lot of good for their town and they did not want to see it go. The company was sold to the American Range and Foundry December 4th with the sale being confirmed December 22nd. The main offices of the American Range and Foundry moved their offices to Shakopee and the business was taken over as the American Range Corporation on January 1st of 1925.

Sadly, fire struck again in early 1925. This time, at the Shakopee Stove Company. On February 3rd at around 2:40am the Shakopee Stove Company caught flame destroying the building, machinery, equipment, heaters, and ranges. Only one new steel warehouse was saved and this was only due to a rapid response keeping the fires contained to the other buildings. That warehouse along with the 150 stoves and heaters inside of it were the only things to survive. The losses amounted to $40,000 dollars and was, again, only parially covered by insurance. Unlike the Minnesota Stove Company, the Shakopee Stove Company did not recover and its story ended there. This is particularly unfortunate seeing as plans were in place to merge Shakopee Stove Company with the American Range Corporation. An article from a February 13th edition of the Shakopee Argus stated, “A consolidation of the Shakopee Stove Company with American Range Corporation was to have been effected last Saturday but was held up temporarily and would have gone into effect this week.” After only 10 years, the Shakopee Stove Company was gone leaving the American Range Corporation to meet demand.

By 1927, the American Range Corporation was facing the same troubles that the Minnesota Stove Company had faced. A headline from the May 26th edition of the Argus Tribune declared, “Local Industry Captialized at $500,000, Employs 175 Men Has $25,000 Monthly Payroll, Capacity 75 Stoves Daily, Production Fails to Keep Step with Demand.” Despite its struggles, the American Range Corporation continued to run until May 1931, when it shut down temporarily. Between 1931 and 1933 the factory made efforts to restart but it was unclear if it ever was able to. Reports suggest that there were plans to restart in late 1931 but it would seem that did not happen. On August 10th of 1933, business did start again with owners expressing hope that the restart would not just be temporary. By 1936 business was certainly rolling smoothly as work was done to keep pace with the demand caused by a cold streak. Eventually, the problems of the past caught up with them and supply was not able to meet demand. Instead of continuing the business, it was authorized for sale on April 20th of 1940. The factory was bought for $45,000 by a group in Chicago. Beginning in 1941, the factory space was put to a new purpose of building cots for the military engaged in World War II. The factory never returned to its original purpose.

The Scott County Historical had an exhibit entitled “Stoke the Fire: The Life and Times of the Shakopee Stove” in 1998. Below are some photos of the stoves produced by the Minnesota Stove Company, Shakopee Stove Company, and American Range Corporation as displayed in the exhibit. The white stove in the upper right hand corner is currently on display in the museum.

Written by Tony Connors, Curatorial Assistant.