The sun is shining and the snow is sparkling outside the Scott County Historical Society museum. After several days of fog, folks are out on the street enjoying the snow. A sunny day in winter is delightful, whether you are sledding outside or holed up inside where it is warm. Below, find a selection of seasonal photographs from the SCHS collections. Enjoy the winter!

Downtown Shakopee after a blizzard. C.J. Stunk (seen holding a shovel) and several other men are standing on a shoveled First Ave. Handwritten in pencil on the backside of the image is “Sunday March 12th – 1899. 10 am.

Photograph of downtown Shakopee after a March snowstorm. The photo shows First Avenue looking southeast. 1899.

Two men moving logs on North Meridian Street in Belle Plaine.

Thomas O’Connor delivering mail in Belle Plaine. 1905

Men clearing snow from the roads in Shakopee. 1905.

Postcard of Pond’s Mill in Shakopee during the winter. The card is addressed to Miss Clara Logenfeif of Shakopee but is unused. 1908.

Winter street scene in New Prague, Minnesota, probably a market day. 1914.

The Coller family standing outside their downtown Shakopee home. Seen from left to right are Julius Coller, I, Coe Coller and Julius Coller, II, and their dog (name unknown). 1914.

Holiday decorations inside a Shakopee home. 1915

Women ice skating in Shakopee, most likely on the Minnesota river. 1920.

The exterior of 434 South Lewis Street in Shakopee after a snowstorm. 1927.

Two children wearing winter coats in Belle Plaine. 1928.

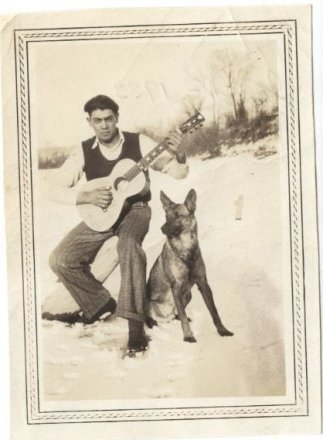

Harry Weldon playing guitar with his dog during winter. 1933.

Arthur Bohnsack with two of his children, Arlyn and June standing in front of their new Chevorlet. Taken in St. Patrick MN. 1940.

Ray and Loretta (Mamer) Robel of Prior Lake sitting in their living room on Christmas. 1950.

Snowy road after a blizzard in Shakopee. 1950.

Christmas card featuring the Pekarna boys. 1954.

LeRoy Lebens shoveling snow outside his Fifth Avenue home in Shakopee. 1955.

Two Shakopee High School students in winter finery. 1958.

Cat in the snow. Shakopee 1959.

Nevins family holiday decorations, 1960

Clark family Christmas photo. 1963

The Minnesota River outside Shakopee. 1965.

Johnson family Christmas photo. 1970

Downtown Shakopee block with piles of snow. Date unknown.

Enjoy the winter!

Compiled by Rose James, SCHS Program Manager