During the Great Depression Scott County, like numerous counties across the nation, was faced with the problem of homelessness. One road to relief was the construction of five “transient camps”, profiled in last week’s Scott County History blog post. These camps were an effective, but short lived solution. The administrative center of these camps was located just outside of Shakopee. Originally constructed in 1934, the Shakopee camp was emptied by 1938. It was determined that the facility would have new life as a NYA, or National Youth Administration camp.

National Youth Administration Recuitment poster, 1941. Work Projects Administration Poster Collection (Library of Congress).

The National Youth Administration was a New Deal program launched in 1935. Similar to work-study programs for college students today, the NYA paid a grant stipend for part-time work to young people between the ages of 18 and 25. Some of this work was in the educational sector, helping out with administrative and maintenance tasks at academic institutions. Other projects provided on-the-job training in fields such as forestry, agriculture and construction. The goal was to provide meaningful paid work to young people that would teach on-the-job skills, giving beneficiaries an eventual leg up in the job market. An added aim was keeping young people from flooding the already strained traditional labor market.

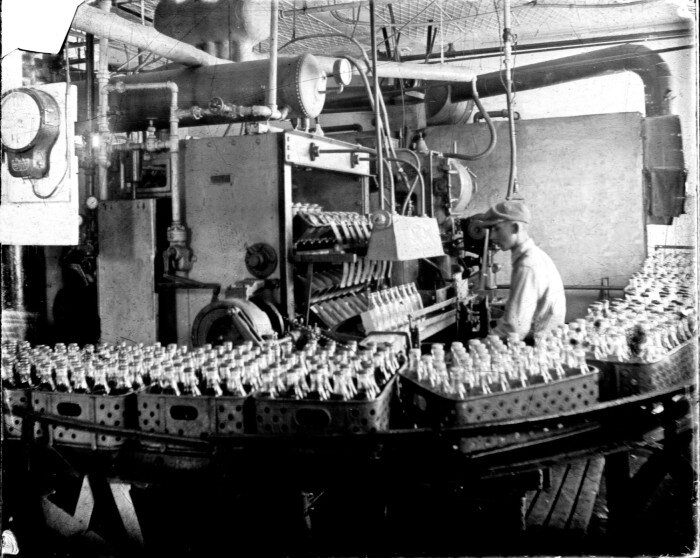

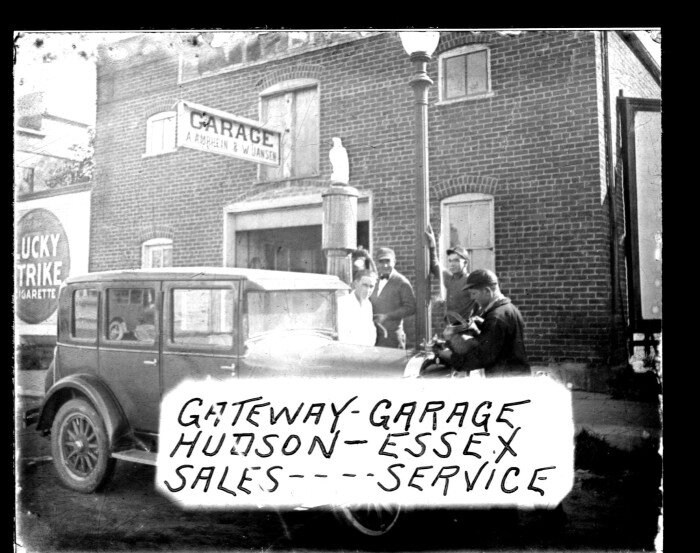

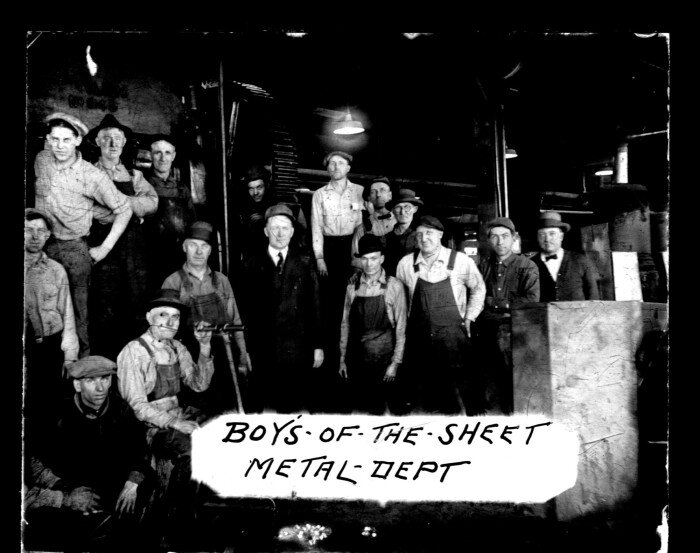

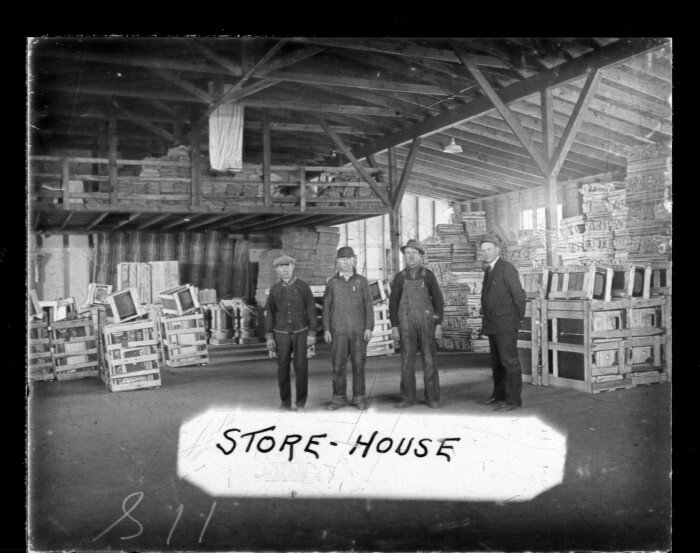

The National Youth Administration Camp outside of Shakopee was a unique affair. It combined the work-study goals of traditional NYA jobs with the housing of the former transient center. The Shakopee Argus-Tribune announced the development of the camp on March 31st, 1938. It described the goals of the program thusly: “…a practical education center for deserving young men between the ages of 18 and 25… it is not like the CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] in that it is non-military. Boys enter on a six-month tenure. They will work a half day and study a half day and draw a small wage. The program is not one primarily of employment but one in which willing youths may be aided educationally”. An official bulletin printed in the April 7th Argus-Tribune formally stated “The primary purpose of this project is not to directly prepare young men for employment but to make possible exploratory experiences in various fields which may lead to self-maintenance and which will better qualify young men for worthwhile home and community life”. The educational opportunities listed were agriculture, auto mechanics, carpentry, welding, forestry, and shoe repair. Basically, the camp provided a vocational liberal-arts education.

Headline announcing the construction of Shakopee’s NYA Camp. From the Shakopee Argus-Tribune, April 7, 1938. SCHS Collections

The camp was limited in who it served. Only males could enroll in the program, and they must “be certified as in need by an approved public relief agency”. Each enrollee drew $30.00 per month, $20 of which provided for room and board, and $10 for the boys and their families. The youths were housed in rough-cut cabins and provided with food in a mess hall, recreational facilities and medical care.

As time passed, opportunities at the camp expanded. On March 20, 1939 the Shakopee Argus-Tribune reported that the camp was producing a radio program entitled “Tangled Lives”. Each week the program presented a dramatized enactment of a problem performed by NYA enrollees. Problems ranged from “Should I apply to College” to “Physical Disability”. After the performance, a team of experts would assemble to share possible solutions with listeners.

On September 1st, 1939 Hitler invaded Poland and, at least in Europe, World War 2 begun. While the US did not officially join the conflict until 1941, rumblings of war could be felt In Shakopee’s NYA camp. On September 14th, 1939 the Shakopee Argus-Tribune announced a $200,000 allocation to train camp youth in airplane mechanics through a program under the supervision of Col. Victor Page. In August of 1940, the camp youth began construction of two seaplane bases that would, upon completion, be shipped where they were needed. The work at the camp was focusing more and more on national defense.

Administrative building of the Shakopee NYA camp. The building was originally Murphy’s Inn, and was located on the site of what is now The Landing. SCHS Collections, 1938

On July 1st, 1941, nearly 5 months before US entry into WW2, the enrollment at the Shakopee NYA camp was suddenly bumped to the staggering number of 544. The order to increase enrollees came from the Office of Production Management in Washington, and specified that the new recruits be trained in defense production. Along with quarters for the new boys, a machine shop and facilities for training in radio operation and communication were added.

By 1942 the United States was firmly entrenched in war. On February 12th, 1942 the Shakopee Argus-Tribune announced that authority over the NYA camp would be formally transferred to the US Navy, who planned to use the facility to train recruits as Navy machinists.

After the end of World War 2 ownership of the camp lands was transferred to the Shakopee Public Schools. The rustic cabins that housed NYA and Navy recruits became rental properties, housing Scott County families until the early 1960s. Interested in visiting the old NYA camp? The ruins of Murphy’s Inn- first the Administration building of the transient camp, then the center of the NYA camp- are currently part of The Landing, a historic site in the Three Rivers Park District.

Written by Rose James, SCHS Program Manager